Molly

How strange that the very first thing I read on my first day of research for CELL was that MND affects men much more than women. How strange that from the very beginning our central character has always been a man, right from the very outside of shaping our idea. I wonder if the two are linked at all? I wanted to find out why MND is more prevalent in men but as I started digging around, it seems that this is one of the many unanswered questions about the disease. The simplest answer, is that they do not know.

All this not knowing, this speculating, this guessing got me thinking about the more tangible side of MND so I started looking into the human qualities, the stuff that we and hopefully the audience, as people, will know, understand and recognise. I was perhaps a little naively shocked that when people contract MND there is no immediate sign that would raise alarm, nothing that is particularly out of the ordinary. I was searching through the MNDA website (http://www.mndassociation.org) and was reading personal accounts of people who have MND. Many of them commented that very mundane and human actions started to happen more frequently, for example, they started to drop things more often or they started to trip over their own feet. These actions, which would not be deemed as strange then build up but slowly, over a passage of time. For me, this was something I could immediately access as I have the experience of doing both of these actions. It hit me that if I started dropping things more often, I would probably think nothing of it at all, I would probably think I was having a bad day, I was tired, I was being clumsy. It is perhaps only in hindsight, only in warped, slowed down memory, with a diagnosis, with a label that one notices them...

How strange that the very first thing I read on my first day of research for CELL was that MND affects men much more than women. How strange that from the very beginning our central character has always been a man, right from the very outside of shaping our idea. I wonder if the two are linked at all? I wanted to find out why MND is more prevalent in men but as I started digging around, it seems that this is one of the many unanswered questions about the disease. The simplest answer, is that they do not know.

All this not knowing, this speculating, this guessing got me thinking about the more tangible side of MND so I started looking into the human qualities, the stuff that we and hopefully the audience, as people, will know, understand and recognise. I was perhaps a little naively shocked that when people contract MND there is no immediate sign that would raise alarm, nothing that is particularly out of the ordinary. I was searching through the MNDA website (http://www.mndassociation.org) and was reading personal accounts of people who have MND. Many of them commented that very mundane and human actions started to happen more frequently, for example, they started to drop things more often or they started to trip over their own feet. These actions, which would not be deemed as strange then build up but slowly, over a passage of time. For me, this was something I could immediately access as I have the experience of doing both of these actions. It hit me that if I started dropping things more often, I would probably think nothing of it at all, I would probably think I was having a bad day, I was tired, I was being clumsy. It is perhaps only in hindsight, only in warped, slowed down memory, with a diagnosis, with a label that one notices them...

Carly

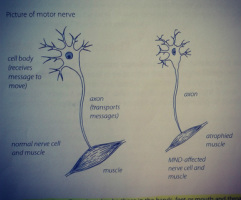

For me, I felt I needed to understand the scientific explanation of MND before I started to research anything else. I knew the disease affected the nerves in the brain and the spinal cord, but how? So, I went to the Templeman Library on the University of Kent campus and started sifting through books trying to understand exactly what happens. To condense, the cell body of a motor neurone receives messages from another cell through its axon, (the signals or messages between neurones are called synapses) creating muscle movement. In a person with MND, the nerves become damaged, meaning their muscle control weakens and the muscle itself wastes away.

"The muscles first affected tend to be those in the hands, feet or mouth and throat..." (www.mndaassociation.org)

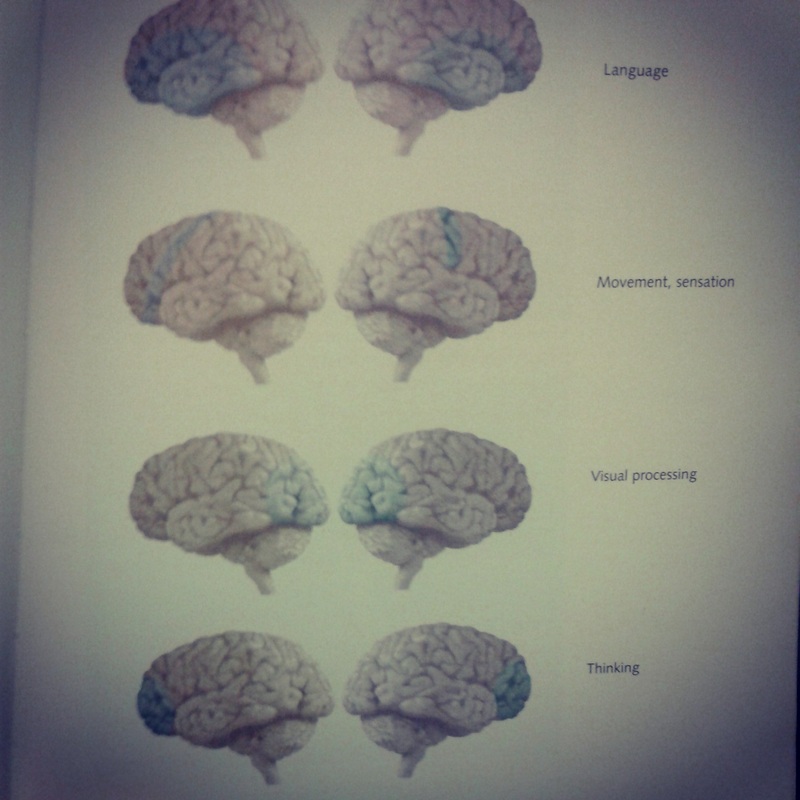

When reading further about the symptoms on MND, I got stuck on changes in speech. Speech errors such as malapropisms (e.g. a spoonerism - You have hissed all of my mystery lectures) and tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon become more prevalent, some consonants become harder to say (p, b, t, d, k and g), the voice begins to sound hoarse, low pitched and monotonous. In The Student's Guide to Cognitive Neuroscience, Jamie Ward explains: "Speech production normally only exists when someone else is around to engage in the complementary process of speech recognition." This made me think a lot about our main character. They will have to have someone else to engage with through speech in order for us to show its decline, whether that be directly at the audience or with another character on stage is something for us to look at in rehearsals (we are all very unsure about a speaking puppet though...)

After the science reading, I began to think of our creative process. Discovering these tips from Doctors for MND patients, I thought they would help us as a collaborative company throughout the rehearsal process, giving us something to 'check in on':

For me, I felt I needed to understand the scientific explanation of MND before I started to research anything else. I knew the disease affected the nerves in the brain and the spinal cord, but how? So, I went to the Templeman Library on the University of Kent campus and started sifting through books trying to understand exactly what happens. To condense, the cell body of a motor neurone receives messages from another cell through its axon, (the signals or messages between neurones are called synapses) creating muscle movement. In a person with MND, the nerves become damaged, meaning their muscle control weakens and the muscle itself wastes away.

"The muscles first affected tend to be those in the hands, feet or mouth and throat..." (www.mndaassociation.org)

When reading further about the symptoms on MND, I got stuck on changes in speech. Speech errors such as malapropisms (e.g. a spoonerism - You have hissed all of my mystery lectures) and tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon become more prevalent, some consonants become harder to say (p, b, t, d, k and g), the voice begins to sound hoarse, low pitched and monotonous. In The Student's Guide to Cognitive Neuroscience, Jamie Ward explains: "Speech production normally only exists when someone else is around to engage in the complementary process of speech recognition." This made me think a lot about our main character. They will have to have someone else to engage with through speech in order for us to show its decline, whether that be directly at the audience or with another character on stage is something for us to look at in rehearsals (we are all very unsure about a speaking puppet though...)

After the science reading, I began to think of our creative process. Discovering these tips from Doctors for MND patients, I thought they would help us as a collaborative company throughout the rehearsal process, giving us something to 'check in on':

- Recognise what was and what is now

- Remain involved in the world around you

- Retaining a sense of humour is life-enhancing

RSS Feed

RSS Feed